Bringing Broadband to the underserved is a huge task that has been in the news for years. Yet, there is still no plan that looks to be the solution.

Rural Broadband subsidies are meant to bring Broadband to unserved areas of the US. The current FCC definition of broadband is for 25Mbps download speed. There have been multiple programs allocating funding for Rural Broadband including CAF 2 and the new “shiny” plan the RDOF. As the US distributes billions through the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund (RDOF), which the FCC has called its "largest investment ever to close [the] digital divide" are we really going to make progress?

In the past the Universal Service funds at the state and federal level have supported rural phone service that had included some DSL service. One of the problems with all of this is that politicians, while well intentioned, get their mileage by grandstanding their support yet not understanding what is the best way to handle this issue. So, funds are appropriated yet we still have problems. We need accountability.

One of the roadblocks to accountability is a national and state map of where there is currently broadband and where it does not exist.

A coalition of Republican Senators is pushing an ambitious $20 billion plan on top of billions of dollars in funding already earmarked for unserved communities, a fundamental flaw remains in not knowing where the problems lie. The faulty FCC national broadband map has essentially made millions of Americans without fast internet "invisible," as Microsoft put it, and unless the data improve, they're likely to remain so.

The broadband mapping problem goes back to the early days of the internet, when the Telecommunications Act of 1996 required the FCC to collect semiannual data from providers about which ZIP codes they serviced. But the agency didn't publicly disclose the internet service providers in each area.

Thirteen years later, the government tried to make the information more transparent. A provision of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, signed by President Barack Obama, mandated the development of a National Broadband Plan and the creation of a US broadband map by mid-February 2011.

Well, February 2011 has come and gone and there is not a good map. BUT, where were the taxpayer funds spent?

To build the map, internet service providers twice a year give the FCC what's called Form 477 data that details coverage areas and speeds. But the FCC doesn't check the data; it just relies on the ISPs to report accurate information. And the speeds that service providers list are what their advertised maximum speeds are, not necessarily the everyday reality. Pricing data is kept confidential, which means broadband speeds may be available but at very high rates.

In January 2021 the FCC declared they will have a “mapping committee” which will have data in 2022. Yet we have allocated billions of taxpayer dollars to be spent in 2021?

The current RDOF program and its predecessor program CAF 2 have had “issues” according to Christopher Ali, Associate Professor at the University of Virginia.

Frontier and CenturyLink informed the FCC that they will not meet certain Connect America Fund CAF II deployment milestones. Carriers that accepted CAF II broadband funding were supposed to have reached 80% of locations in every state for which they are receiving support by December 31, 2019, but both carriers will miss that milestone in certain states. Astonishingly, these two carriers were not required to refund the money received for services not performed.

Frontier has since gone through bankruptcy and CenturyLink has changed their name.

Jeff Seal, National Rural Broadband Analyst, noted, “I’m proud of the roadmap we created and the amazing progress we’ve made over the last decade. However, we still have a way to go before we finish the job. During the coronavirus pandemic, we are seeing more than ever how necessary robust and affordable broadband is to the future of American life, education, jobs, and medical care,” Jeff said. “We need to close the digital divide that has been emphasized by the pandemic, as professional and personal life has largely shifted online.”

“From telehealth to remote learning to teleworking, high-speed internet is essential in our day-to-day lives. We must make broadband affordable and accessible for all Americans.”

“We look forward to working to modernize aspects of the law to accelerate broadband deployment to unserved areas and promote continued investment and innovation in the communications sector,” Mr Seal added. As more and more stakeholders express concern that some RDOF (Rural Digital Opportunity Fund) winners will not be able to deploy rural broadband meeting the service parameters to which they committed, one stakeholder has an interesting idea for what to do about this. Perhaps an RDOF amnesty program would be appropriate, suggested Jonathan Chambers, a partner with Conexon.

Conexon formed the Rural Electric Cooperative Consortium, a bidding entity representing 90 cooperatives that, collectively, won $1.1 billion in the auction — and while members of that group appear well-positioned to meet their buildout requirements, that may not be true for all winners.

Many have expressed concerns about some winners. There is a real question of whether “companies that haven’t built tens of thousands of miles of fiber will be capable of building thousands of miles over a short period of time,” noted Chambers.

Chambers is one of several stakeholders that have singled out LTD Broadband, which won the most funding — $1.5 billion — in the auction, as a company that won funding to serve considerably more locations than it already serves. Traditionally the company has offered fixed wireless and fiber but bid to deploy gigabit-speed fiber for its RDOF buildouts.

LTD Broadband CEO Corey Hauer in late December, who said, “We have a history of very rapid growth. We expect that to continue. We have met challenges of growth and scale as we’ve grown.”

Some other big RDOF winners bid to deploy gigabit fixed wireless and/or gigabit fiber, and some stakeholders, including Chambers, have questioned whether fixed wireless will be a viable means of providing gigabit service in rural areas.

Although manufacturers claim it will be possible, others argue that the technology has not yet been proven in rural areas.

Chambers said he has heard from auction participants that some participants that initially wanted to use gigabit fixed wireless for their auction bids were told they couldn’t bid to use fixed wireless at the gigabit speed tier. (The auction awarded funding to the company that committed to deploying broadband at the lowest level of support, but a weighting system favored bids to deploy gigabit service.)

It’s not clear why some companies allegedly were allowed to bid gigabit fixed wireless and others weren’t. One possibility is that different FCC staffers responded differently to bidders after reviewing their initial applications.

The upshot is that “you can already see there are companies that seem to be preparing for the great bait-and-switch.” Some companies that bid to deploy gigabit fiber will try to get the FCC to allow them to use fixed wireless instead.

Some of the winning bids in the RDOF rural broadband funding auction were for unrealistically low levels of support and the net result could be that those areas do not get service, according to two of the rural electric cooperatives that bid in the auction.

The cooperatives discussed their concerns on a virtual press conference organized by the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association (NRECA), where NRECA urged the FCC to closely scrutinize the long-form applications submitted by auction winners.

The Rural Digital Opportunity Fund auction awarded $9.2 billion to cover some of the cost of deploying broadband to unserved areas using a reverse auction approach. Funding went to the bidder that committed to deploying service at the lowest level of support, with a weighting system favoring bids to deploy faster, lower-latency service. The vast majority (85%) of winning bids call for the recipient to deploy service at gigabit speeds.

Sam Pruitt CEO of Render is one of the companies that works with NRECA and has proven their capabilities to deliver a quality product.

Midwest Energy Communications (MEC) won $37 million in the RDOF auction as part of a consortium organized by the National Rural Telecommunications Cooperative (NRTC). The company will use the funding toward the full $165 million cost of a fiber-to-the-premises deployment that will make service available to 40,000 locations in rural Michigan.

The company dropped out of bidding for 30-some census block groups when it was underbid by a company bidding to use fixed wireless service in the fastest speed group—1 Gbps.

“MEC contends that the blocks were lost to other bidders that cannot and will not be able to deliver service at the level claimed in the tier they bid,” said Bob Hance, MEC CEO, on the virtual press conference webcast.

He added that “wireless technology is not capable of providing gigabit service, even in the most ideal circumstances.”

People in the census blocks that MEC lost are “likely to obtain inferior service for the next several years,” Hance said.

Manufacturers of fixed wireless equipment say the technology can support gigabit speeds. But NRTC and NRECA have issued a white paper detailing its concerns about the ability of fixed wireless technology to support gigabit service.

In the RDOF auction, the NRTC consortium bid fixed wireless at “responsible speeds” of 100 Mbps in some areas, noted Tim Bryan, CEO of NRTC, on the webinar.

“We lost in all those area,” he said.

Another RDOF bidding story came from Mike Malandro, president and CEO of Maryland’s Choptank Electric Cooperative. Choptank bid to provide service using fiber broadband in unserved rural areas of the state but dropped out of the auction when it was underbid by a “very small company.”

Malandro subsequently confirmed that the company was Talkie Communications which, according to FCC data, plans to use FTTP for its deployments.

“The money available was not enough to commit to serving the area in a six-year time frame,” said Malandro of Choptank’s decision to drop out. “Prior to the RDOF auction, I had great hope for [closing] the digital divide quicker, but I now feel that the RDOF has done the opposite.”

By taking areas with dubious winning bids off the table, the auction “will leave rural Maryland homes and businesses behind,” according to Malandro.

MEC, Choptank and NRECA join a growing group of stakeholders that have questioned how the FCC handled the RDOF auction. Others that have expressed concern include NTCA – The Rural Broadband Association, more than 150 federal legislators, rural lender CoBank and Windstream CEO Tony Thomas.

Some stakeholders have argued that the FCC should have vetted bidders and business plans more closely before beginning the auction. Those stakeholders have urged the commission to closely scrutinize the long-form applications that winning bidders are required to submit.

Jim Matheson, CEO of NRECA, added his voice to those stakeholders today.

“Every bid should be thoroughly evaluated” and there should be “more transparency” about that process, Matheson said. He also urged the FCC to impose tighter rules for the planned Phase 2 RDOF auction.

Customers of the SpaceX Starlink satellite broadband service are likely to receive inferior service in areas for which SpaceX won funding through the RDOF (Rural Digital Opportunity Fund) auction, according to a SpaceX service report commissioned by NTCA – The Rural Broadband Association and the Fiber Broadband Association (FBA). The report is based on a technical analysis conducted by technology researchers at Cartesian.

SpaceX was one of the biggest winners in the RDOF auction, which awarded funding to the company that committed to bringing broadband to unserved areas for the lowest level of support, with a weighting system favoring bids to provide faster service and lower latency. SpaceX won $885 million in the RDOF auction to cover some of the costs of making broadband available to people in unserved areas of 35 states.

885 million of your tax dollars will be spent to deploy something that charges 99 dollars per month and costs roughly 500 dollars to pay for premise equipment.

Unlike traditional satellite providers, SpaceX uses non-geostationary satellites that are closer to Earth to minimize latency. The company committed to deploying low-latency service at speeds of 100 Mbps downstream and 20 Mbps upstream, but the Cartesian report questions whether the company will be able to do that consistently.

SpaceX Service Report

As NTCA and FBA note in a letter to the FCC accompanied by the report, “If SpaceX were to engineer its network to serve only the requisite number of RDOF locations and then serve no other locations (i.e., the network is engineered to serve 70% of 642,925 locations), Cartesian estimates that 56% of SpaceX’s RDOF locations in the low capacity case (average bandwidth usage of 15.3 Mbps per location) and 57% of locations in the high capacity case (average bandwidth usage of 20.8 Mbps per customer) will experience service degradation during peak times and not meet the RDOF public interest requirements; further, Cartesian estimates that 25% to 29% of locations will receive an average of less than 10 Mbps of bandwidth during peak times.”

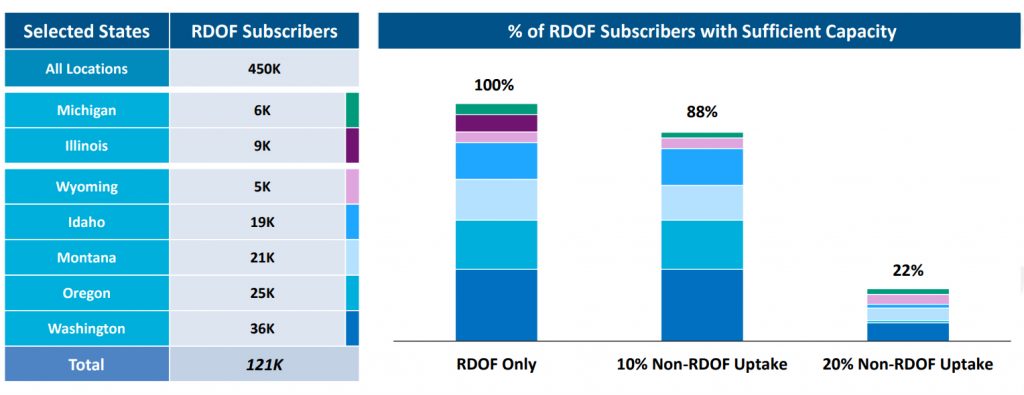

Service would vary from one state to another, with Midwest and Western states seeing adequate service assuming SpaceX only serves RDOF locations, even in the high-capacity case, according to the report. But Eastern states would not receive sufficient bandwidth even in the RDOF-only low-usage scenario.

It would seem unlikely, however, that SpaceX would dedicate its entire capacity for an area to RDOF but instead would also seek to serve other customers, the associations note in the letter. The associations note that SpaceX public announcements indicate that the company is exploring service for U.S. defense applications, industries such as oil and gas exploration and vehicle broadband.

If SpaceX were to devote just 10% of its capacity to non-RDOF subscribers, the percentage of customers receiving sufficient capacity would decline. Even in the best-served Midwest and West, only 88% of customers would receive sufficient capacity at the 20.8 Mbps usage level. If 20% of SpaceX capacity were to go toward non-RDOF locations, the 88% figure would drop dramatically to just 22%, according to Cartesian’s SpaceX service report.

20.8 Mbps Capacity. Source: Cartesian, FCC

And if 50% of SpaceX capacity overall is allocated to non-RDOF locations, only 5% to 8% of RDOF locations would receive sufficient bandwidth during peak hours, according to the NTCA and FBA letter.

SpaceX did provide quite a bit of information about its service in a recent letter to the FCC, but did not include detailed capacity estimates.

In their letter, NTCA and FBA note that SpaceX may have provided the FCC with additional confidential information that might yield different results. The associations added, though, that they “hope at the very least that an analysis of this kind proves useful to the commission as it considers how to structure and undertake its own review of SpaceX’s long-form applications.”

The Cartesian analysis “is intended to be instructive rather than conclusive in demonstrating the detailed level and types of analysis needed to evaluate the capabilities of a low-earth orbit satellite system to deliver on RDOF commitments,” the letter states.

RDOF Amnesty Program?

Chambers and other critics have said the FCC should have requested more information from auction applicants prior to the auction. Chambers hopes the FCC will make up for that as part of the long-form application process, which winners are in the middle of now.

“Financial projections should include construction costs, including the miles of fiber you expect to build – if someone doesn’t know that number, that’s a red flag,” Chambers said, noting that members of the Rural Electric Cooperative Consortium already secured fiber and labor for their RDOF gigabit fiber build-outs.

He believes some winning bids could and should be rejected but that will only occur if the FCC changes the way it reviews things.

“The way they review applications is by looking at descriptions of the networks; they don’t look at capability to build,” he said.

Chambers sees a possibility that the review process could change, considering the recent administration change. As things stand now, however, any funding pulled back from the provisional winner would likely roll into the Phase 2 RDOF auction, which won’t happen until the FCC completes its revamp of broadband availability data collection and analyzes that data, which could be a time-consuming process.

Chambers offered some interesting alternative ideas. One idea, he said, might be to offer RDOF amnesty to any auction bidder, which would give over-zealous bidders the option of bowing out gracefully without encountering penalties.

And perhaps the FCC wouldn’t have to wait until the Phase 2 auction to award the funding returned by those accepting amnesty. Perhaps the commission could conduct a separate auction for areas turned back, Chambers suggested.

Universal Service Funds

The Texas Telephone Association, which represents about 50 rural telecom providers, is suing the state of Texas in connection with the state’s Universal Service Fund (USF). According to a report published by media outlet The Texan, the state owes the providers $60 million in unpaid USF subsidies.

The Texas USF covers some of the costs of providing service in high-cost rural areas. Funding for the program comes from a 3.3% charge on intrastate calls, The Texan reports, and through that mechanism, the state over the last six months only collected about 66% of the funding needed for the program.

The shortfall is projected to be about $80 million for 2021 and more than $140 million in 2022. The lawsuit asks for a court order requiring the state to remit missed payments to the providers and issue a permanent injunction to require the state to fulfill future obligations.

The funding raised through the 3.3% charge is insufficient because of “a deterioration in collections caused by a decrease in the types of calls that qualify for the fee” – an apparent reference to declining voice revenues that telecom providers nationwide have experienced.

Do the US ratepayers really owe monthly funding to rural carriers for something already installed? There are many ideas on this subject but if the carriers and end users cant pay for what they receive it really amounts to a subsidized welfare program paid for by the rate payers and tax payers of America. Their response likely will be, “So, where is my check?

In June 2020, the Texas Public Utilities Commission considered a motion to increase the charge collected against intrastate calls to 6.4%, but the motion was rejected. If the motion had passed, the fee would have increased from about 50 cents a month per customer to 95 cents a month, which some commissioners said would be a hardship amid the COVID crisis.

One commissioner reportedly called the fee an “almost irrational singling out of this group of people who we would be taxing.”

Beyond Texas

It will be interesting to see how the Texas Universal Service Fund quandary is resolved, because the situation there underscores similar issues that have arisen at the federal level. The federal Universal Service Fund also is funded through a charge on phone calls – in this case, on interstate calls.

One point is true in this matter-This is not a fee that the Government “mandated” rate payers to be on the hook for. The carriers are misleading the ratepayers in the matter.

Unlike in Texas, though, the charge isn’t a fixed one. Instead, the charge is simply increased as needed to cover program costs. As a result, it now exceeds 30% of revenues on interstate calls.

At the federal level, a variety of suggestions have been made for how to address this – including funding the program through money raised in spectrum auctions or funding it through general tax revenues.

The NTIA revealed additional details on its Tribal broadband program, officially known as the Tribal Broadband Connectivity Program (TBCP). The program will provide up to $1 billion to improve broadband on Tribal lands.

According to a recent report from ILSR, citing FCC data, only 60% percent of tribal lands in the lower 48 states had high-speed Internet access.

The TBCP is funded from the recent Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021, which also funded other broadband programs, including $3.2 billion for an Emergency Broadband Benefit program. These programs aim to support communities impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic by helping improve access to broadband.

The TBCP program stipulates that grant funds be prioritized for unserved areas. Specifically, the NTIA Tribal broadband program will provide funding for the following:

- Broadband infrastructure deployment, including support for the establishment of carrier-neutral submarine cable landing stations

- Affordable broadband programs, including:

- providing free or reduced-cost broadband service

- preventing disconnection of existing broadband service

- distance learning

- telehealth

- digital inclusion efforts

- broadband adoption activities

Eligible entities for the TBCP program include: 1) Tribal governments; 2) Tribal colleges and universities; 3) the Department of Hawaiian Homelands on behalf of the Native Hawaiian Community, including Native Hawaiian education programs; 4) Tribal organizations; and 5) native corporations as defined under Section 3 of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act.

NTIA wants to make grants available through the Tribal broadband program as quickly as possible. The agency is holding a series of consultation sessions this week on Feb. 10th and 12th to gain tribal input on the program. Tribal leadership and their designees are encouraged to participate.